But 2020 would surprise me again. Just as I had been mysteriously rejected, however, I submitted my application again and was lo and behold, approved to return home! I was even fortunate enough to secure one of the last flights before all transit between China and Singapore was terminated in March. I was one of the few lucky ones – I later learned that there were many others who failed to get MOM approval or secure flight tickets after multiple attempts.

幾經周折,總算順利回坡,在住處開始了十四天大門不邁的隔離生活。作為從中國回來的重點監測對象,基本每天都會有MOM的工作人員打視頻電話給我。據說如果沒有及時接電話證實自己乖乖坐在家裡的小板凳上,還有可能被吊銷工作簽證。

I made my way back to Singapore eventually and began my mandatory 14-day home quarantine. In stereotypically Singaporean fashion, I was closely monitored during this time: Government officials checked in daily via video calls. I was told ominously that my work visa could be revoked if I failed to answer the calls promptly.

在家隔離的日子一直在想,不同國情下國家政府和居民(從公民的角度又是另一回事)間最有效的信任關係應是怎樣的。誠然,在這樣的特殊時期,疫情的嚴格防控無法單純建立在信任的基礎上。

Quarantine gave me ample time to ponder how an effective trust relationship should be established between governments and foreign residents (though a citizen’s perspective would likely be different). Governments cannot ensure people’s safety during such an unprecedented public health crisis by simply trusting that everyone will behave sensibly.

確實也有很多在隔離期出門被抓到了的案例。不過這也說明即使有每天不定時視頻電話的牽制,也無法完全保證接過電話的人不會出門。因此,這些措施本質上是防君子不防小人,但從效果上來看,這項政策恐怕既讓君子體會到了不受信任的感覺,又沒能填補小人可以鑽的空子。而且,在那疫情開始發展的幾個月里,公共機關每個人手都如金子般珍貴。在這樣的情況下,讓政府工作人員給在家隔離中的幾百上千號人進行每天五分鐘的視頻通話是不是最行之有效的辦法,在我看來還是有待商榷的。

There were cases of people caught wandering around the streets and putting others at risk when they were supposed to be in quarantine. However, the existence of such rebels also means that even if people in quarantine were spot-checked every day, they could still break the rules if they so intended At the end of the day, policies like this seem to only discipline those who are already disciplined. What is worse is that the reasonable and disciplined might feel a lack of trust from this measure, while the rule breakers would still get their opportunities to go out in between the video calls. Therefore, I』m not sure whether these daily five-minute calls to thousands of quarantined individuals is the most effective measure. Moreover, the time spent by MOM staff in conducting the calls must be a precious resource for the government during such a crisis.

同樣,單方面宣布拒絕與否,不提供任何溝通渠道和調整日程的空間,新加坡政府讓特殊時期因為各種各樣的家庭和工作原因想要儘快回到新加坡的長期居民更加焦灼。如果是為了人群的分流,我不太清楚新加坡為什麼沒有採取批准合格的申請但是安排申請者不同入境時間的方法。這樣政府可以規劃每天入境人流量的同時,讓申請者可以更好地安排交通與住宿。單方面通知拒絕或是限時許可,意味著特殊時期的每個入境申請者的旅行安排都面臨很大壓力。

Similarly, the one way communication of both the MOM rejection and the non-negotiable three-day limit certainly did not help already uneasy and anxious travelers during a looming pandemic (COVID-19 was officially declared a pandemic on 12 March). I wondered why other more accommodating policies were not adopted. Qualified applicants could, for example, have been granted the approvals that they deserve while also being assigned specific time periods for entry.

從我二月末回到新加坡到現在已經將近五個月,而後來的新加坡又經歷了疫情的高速蔓延和封城阻斷。現在正在解封的第二階段,很多限制措施正在逐步放寬,不過最近疫情又出現了反彈。我相信我們總會找到對抗疫情的更持久解決辦法,但希望在這次危機中暴露出來的一些溝通與信任的缺失不要在未來一切走向新的平衡的時候被遺忘。

It has been more than five months since I returned to Singapore in late February. During that time the country experienced soaring infection rates and subsequently implemented a national circuit breaker. Although the situation has not yet stabilised, I believe we will eventually find a way to sustainably cope with the pandemic. However, I hope that we will also take time to reflect on the long overlooked issues of communication and trust exposed by the crisis, even after we finally adjust to the post-pandemic 「new normal」.

面對疫情防控的壓力,國家對個人的保護和支持顯得愈發重要,因此有許多人認為這場疫情帶來了「國家集體主義的回歸」。值得注意的是,不同個體獲得的保護和支持並不相同,保護支持的具體內容、方式形式取決於個人和集體之間的關係。

The COVID-19 crisis, many argue, has led to the 「return of the state」. During a crisis, one as multifaceted and all-encompassing as this one, the state’s provision and protection become ever more essential. But that provision and protection is selective, determined by our relationship to the state. No wonder then, that the pandemic has left migrant communities disproportionately affected.

新加坡政府的相關政策就是一個例子。其保護和支持的資源分配主要基於財務和經濟上的考量,忽視了很多外籍居民的權利。由此也帶來諸多問題,例如對被社會邊緣化的客工的忽視。而這一忽視對新加坡的抗疫造成了巨大的影響——直接使之從抗疫模範變成了東南亞首個病例破萬國家。詳見我們兩周前的推送(新加坡:防疫「典範」的盲點)。隨著情況的惡化,新加坡政府「保護和支持」的排他性也越發明顯。

Singapore, for instance, offers protection in a calculated, almost mercenary, manner. The city-state’s neglect of its foreign workers, who』ve lived on the periphery of society, gained Singapore yet another accolade -- from author of the world’s 「COVID-19 Playbook」 in February to Southeast Asia’s largest COVID-19 hotspot by April 2020. As the situation deteriorated, it became clear that the state’s full protection extends only to a select group: Citizens and Permanent Residents.

就連作為高端人才在新加坡留下工作的外籍居民也直觀地感受到了這樣的排他性。當然,這不是新加坡獨有的現象,其他國家,例如日本和紐西蘭也限制了持有工作簽證、為其納稅的外籍居民的入境。

Thus even 「expatriates」, the highly mobile, 「highly-skilled」 migrants, have felt the squeeze. This is by no means a Singaporean phenomenon: countries from Japan to New Zealand have closed their doors not only to travellers but to visa-holding, tax-paying residents.

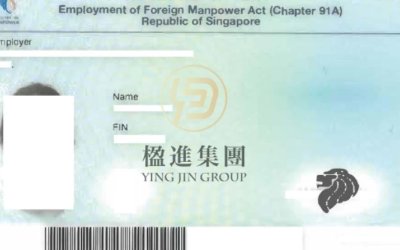

在前兩周的推送里,我們聚焦了新加坡低收入客工群體的困境;這周,我們把目光轉向一位在新加坡工作的中國籍「高端人才」Rae的故事。因為疫情突如其來的層層阻礙讓Rae深刻感受到了她作為外籍居民這一身份的脆弱,以及相關的信任、溝通、約束等一系列問題。也促使我們更全面地反思由科技進步和全球化所成就的勞動力流動性和其背後的脆弱性。